By Rayees Ahmad Kumar

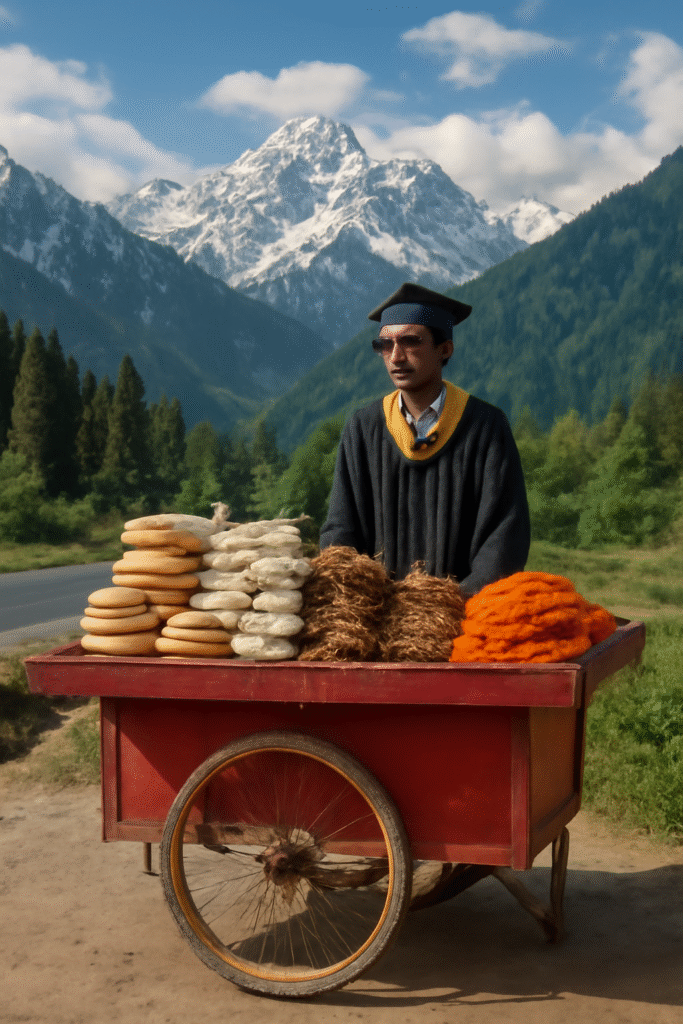

A striking video recently swept across social media: a PhD scholar standing behind a cart, quietly selling dry fruits, surrounded by microphones and phones. The self-styled reporters who flocked to him weren’t there to document his resilience, but to bait him with shallow, mocking questions, reducing his struggle to clickbait. For the young man, it was not just an intrusion but an exposure of humiliation. For society, it was a stark reminder of the disillusionment of Kashmir’s educated youth—individuals who invested their best years in study only to find themselves stranded in an unforgiving job market.

The clip went viral within minutes. Comments poured in, most from people who never paused to consider what it means to invest years in higher education only to end up vending goods on the roadside. Behind the laughter was a harsh reality: thousands of young men and women in the Valley, equipped with postgraduate degrees, NET/SET qualifications, even doctorates, are left navigating lives far removed from the aspirations that once drove them. Their degrees are not just paper—they are symbols of sleepless nights, immense family sacrifices, and parents who emptied savings in the hope of securing their children’s future. Instead, the weight of these degrees has become a quiet burden, leaving many feeling like disappointments in their own homes.

As of January 2025, over 370,000 educated youth in Jammu and Kashmir were officially registered as unemployed—213,007 from Kashmir and 157,804 from Jammu. The true figure is almost certainly higher. A 2024–25 Mission YUVA baseline survey put the youth unemployment rate at 17.4%, nearly double India’s national average of 10.2% Among degree holders, the story is even grimmer: unemployment in the 15–29 age group rose from 21.8% in 2005 to 34.8% in 2022, while female youth unemployment exceeds 57%, the highest in the country.

Ironically, overall unemployment in J&K is not catastrophic—it averaged 6.1% in 2023–24 But these numbers disguise the despair of the educated class. It is not the unskilled but the highly qualified who are being pushed into corners. PhDs and postgraduates are ending up behind carts, in poultry sheds, or teaching in private schools for salaries that barely cover bus fare.

For those who manage to enter higher education as contractual lecturers, the experience is less an achievement than an extension of struggle. Paid far below UGC norms, with no job security and an ever-expanding workload, these lecturers live month to month. There is no absorption policy, no clear path to permanent employment, no acknowledgment of years of service. After shaping generations of students, they return home unable to provide stability for their own families. Inflation ensures their salaries stretch thinner each year. For many, the decision to accept a contractual post is not about career building but survival.

The scale of desperation can be measured in numbers. When the Jammu and Kashmir Services Selection Board announced recruitment for roughly 4,000 constable positions, an astonishing 550,000 applicants applied. Each vacancy drew more than a hundred hopefuls. In urban areas, nearly one in three youth are unemployed, and among women the figure hovers at an alarming 53.6%—the highest female unemployment rate anywhere in India. These are not just statistics; they are markers of a social crisis.

The fallout reaches beyond economics. With financial instability blocking prospects, late marriages are becoming a norm. Families hesitate to commit when steady incomes are absent, leaving many in their thirties still searching for stability before they can think of building households. This social delay compounds the emotional toll, adding frustration to already fragile self-worth. For parents, the sight of their educated children languishing without jobs becomes a source of silent grief.

Authorities are not blind to the crisis. Since 2021, the administration has launched an array of schemes—Mumkin, Tejaswini, Mission Youth, PMEGP, REGP—intended to foster self-employment. Together, they have generated nearly 958,000 opportunities, including 136,000 in 2024–25 alone. Mission YUVA alone aims to create 135,000 enterprises and 450,000 jobs over five years. Employment fairs and entrepreneurship initiatives are increasingly promoted as alternatives to the shrinking pool of government jobs. Even rural employment schemes like MGNREGA have seen expansion, providing 30 million person-days of work.

Yet ambition doesn’t always equal execution. Many educated youth see these schemes as short-term relief, not lasting solutions. The Valley’s private sector remains underdeveloped, industries thin, and tourism still vulnerable to disruption. Without structural investment and genuine industrial growth, educated unemployment risks becoming a permanent feature of the economy. The National Education Policy 2020, with its stress on skill-based learning, offers promise but cannot bridge the gap overnight. The need is not just for skills, but for platforms that value and absorb them.

This is why the viral video of the PhD scholar struck such a chord. He is not an outlier but a symbol—of degrees turned into burdens, of institutions unable to deliver, of families stretched between pride in education and despair at its futility. Mocking such stories dehumanizes a generation already weighed down by systemic failure. What these young men and women need is not ridicule but empathy; not voyeurism but serious attention; not empty slogans but structural reform.

The choice before us is stark. We can either continue treating the struggles of educated youth as spectacles for fleeting amusement, or we can confront them as urgent calls for action. To dismiss their plight is easy. To understand it is harder. But to act—compassionately, boldly, and systemically—is the only way forward. Because when education becomes a trap and ambition curdles into despair, the cost is not borne by individuals alone. It is society itself that pays the price.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this newspaper