The Centre imposes emergency fare caps after a week of mass flight cancellations and steep price spikes, aiming to stabilise domestic air travel.

By Ajaz Rashid

In early December, as holiday bookings peaked and families finalised travel for weddings and work, India’s domestic skies turned chaotic. Thousands of flyers found their plans upended by a wave of cancellations at the country’s largest carrier, and last-minute fares for remaining seats spiked into the tens of thousands of rupees. The government’s answer was swift and decisive: impose temporary maximum fares on non-business domestic economy tickets and warn airlines against opportunistic pricing until operations stabilise. The move — a throwback to measures first used during the pandemic — has brought relief to many passengers but also reopened debates about market discipline, enforcement and the limits of short-term regulation.

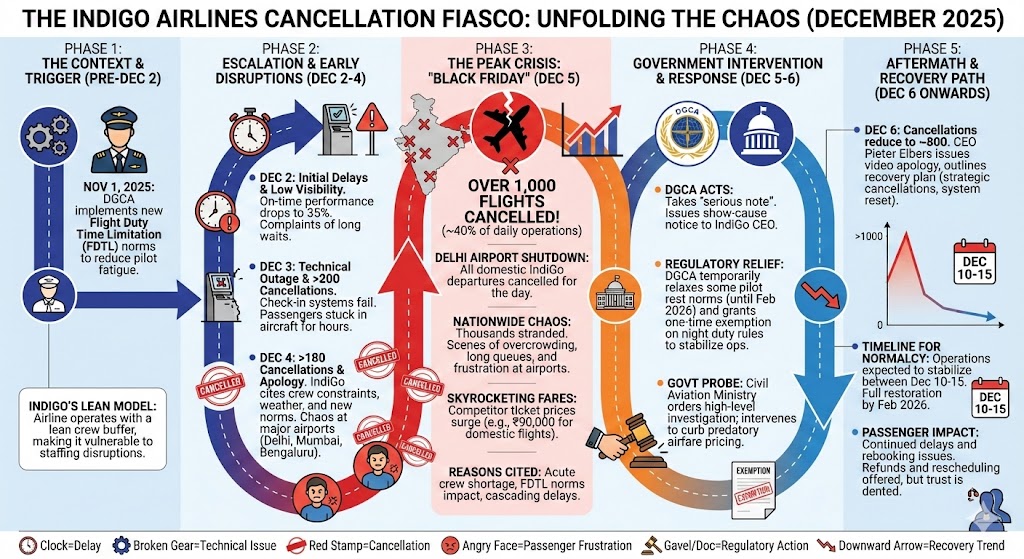

The chaos that forced the ceiling

The crisis began when IndiGo, which controls a dominant share of the Indian market, staggered under a sudden mismatch between crew availability and new Flight Duty Time Limitation (FDTL) rules introduced for pilot safety on November 1. The airline cancelled hundreds of flights over several days, leaving passengers stranded across major airports and triggering a scramble for alternative connections. On the worst days, cancellations ran into the hundreds daily and, cumulatively, into the low thousands over the week as schedules were repeatedly revised. The regulator’s notices, the airline’s crisis committee and government interventions underscored the scale of the operational failure.

When capacity suddenly shrinks, ordinary market dynamics can produce brutal price spikes: automatic revenue-management systems and third-party sellers adjust fares not just to demand but to scarcity. Travel managers reported spot quotes for popular hops — Delhi–Mumbai, Bengaluru–Delhi — rising to levels previously unheard of for equivalent economy travel, stoking public anger and prompting ministerial action.

What the government ordered

On December 6, the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) invoked its regulatory powers and issued a directive capping one-way economy fares (exclusive of user development fees, passenger security fees and taxes) by stage length: ₹7,500 for journeys up to 500 km; ₹12,000 for 500–1,000 km; ₹15,000 for 1,000–1,500 km; and ₹18,000 for stages longer than 1,500 km. The cap excluded business class and the regional connectivity (UDAN) scheme. The ministry said the limits would stay in place “until fares stabilise or till further review” and ordered strict adherence, warning of action for violations.

Beyond pure price control, officials also demanded carriers speed up refunds, return baggage and remove rescheduling fees for affected passengers — measures aimed to shore up consumer protection amid the operational mess. The government gave IndiGo short deadlines to normalise certain services and accepted temporary relaxations on some FDTL provisions to help the airline restore schedules.

Fare bands are not new

India last used a similar regulatory leash during the first waves of the COVID pandemic. From May 2020, MoCA imposed minimum and maximum fare bands to prevent prices from spiking when flights resumed after lockdowns; those caps were progressively lifted and formally withdrawn in August 2022 as demand normalised. The December 2025 intervention is therefore an emergency re-deployment of a tool the government knows how to use — but which it has only reached for sparingly in normal times.

Benefits

For immediate relief, the caps do exactly what they promise: they set an upper bound on what an airline or reseller can charge, preventing grotesque gouging in the short term. That stabilises budgets for corporate travellers and casual flyers alike, and removes the perverse choice many stranded passengers faced — pay a life-changing premium for a seat or wait indefinitely. MoCA framed the move as a targeted protection of vulnerable travellers — senior citizens, patients, students — and an instrument to maintain “pricing discipline” while capacity is restored.

On a practical level, the caps also support public order at airports. When fares soar wildly, frustrated passengers flock en masse to counters and social media amplifies grievances; capped fares lower incentives for desperate last-minute purchases and can reduce the pressure on airport policing and grievance redressal. Airlines such as the Air India Group publicly capped fares on certain routes proactively, signalling that market players also see the reputational value of price restraint during crises.

Enforcement

MoCA has said it will monitor fares in real time and coordinate with airlines and aggregators. DGCA (the regulator) has issued show-cause notices to airline executives in connection with the disruptions, and the ministry has signalled it could escalate penalties for non-compliance. But practical enforcement requires constant price surveillance across thousands of daily itineraries and multiple sellers — a technically heavy lift that will test the capacity of regulators and the political will to impose fines or other sanctions on major carriers. Reuters and other outlets quoted the ministry promising strict adherence and close monitoring.

What travellers should do now

Travel experts advise passengers to know their rights: if a flight is cancelled, travellers are entitled to refunds, re-accommodation on alternative flights, and assistance as per airline and DGCA guidelines. With caps in place, consumers should compare fares across carriers and booking platforms, insist on written confirmations for rescheduling or refunds, and lodge complaints with the aviation consumer forum or MoCA if they believe they have been exploited. Aggregators like ixigo said they would refund convenience fees for certain cancelled bookings, reflecting the ecosystem’s patchwork response.

The wider lesson

The December intervention illustrates a broader governance dilemma in India’s air travel boom: when a dominant private player stumbles, the systemic ripple effects can force the state back into price regulation, even if only temporarily. The caps buy time and protect cash-strapped passengers, but they do not substitute for long-term fixes — better crew planning, more resilient rostering, fleet flexibility, and robust consumer redressal mechanisms. For now, travellers can breathe easier knowing there is an official ceiling; for the industry, the episode is a stark reminder that operational resilience and public trust are as vital as network economics.

As MoCA’s caps remain in force “until fares stabilise”, the coming days will reveal whether the ceiling becomes an effective buffer or a temporary band-aid while underlying scheduling and capacity problems are addressed. For millions planning year-end travel, the practical question is simpler and immediate: will their tickets cost a capped, sane sum — or will scarcity still find a way to push prices beyond reach? The answer depends on enforcement, airline cooperation, and how quickly flight schedules return to normal.

Leave a Reply