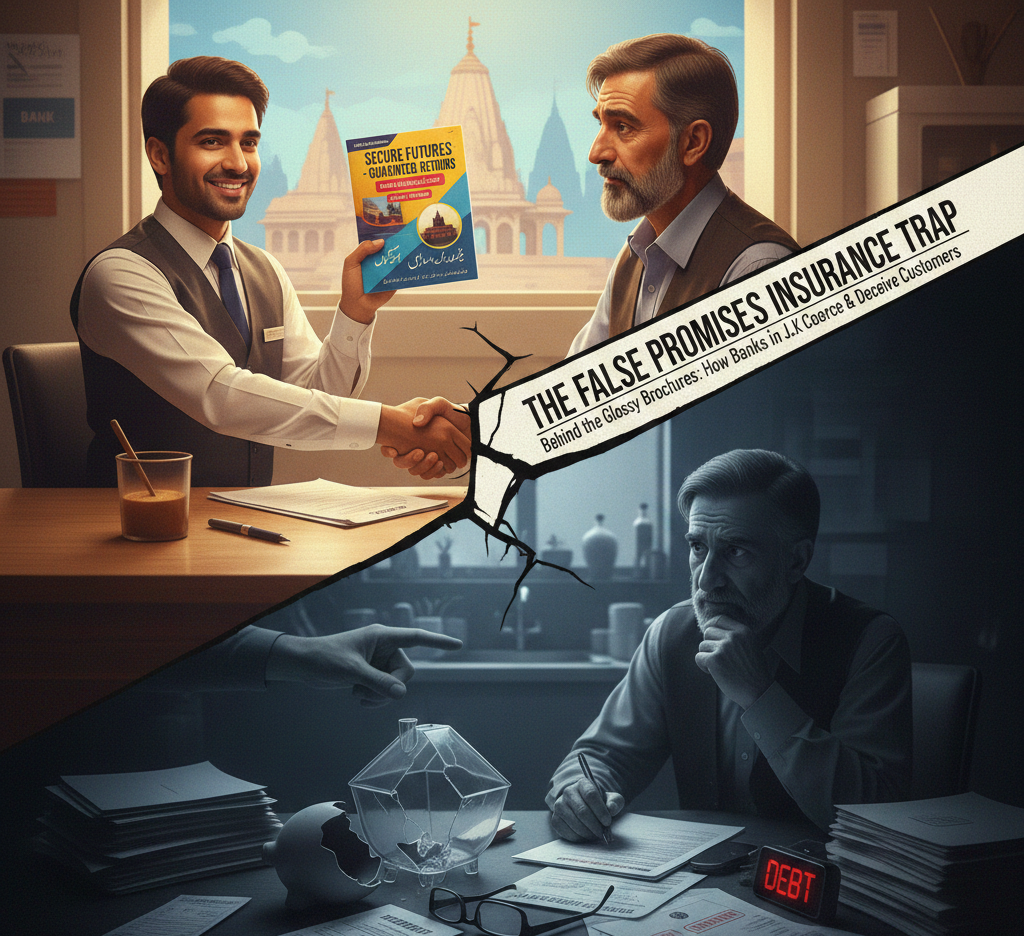

Behind the glossy brochures lies a ‘profitable nexus’ of coercion. As banks in the region prioritize non-interest income to fuel their operational costs, vulnerable borrowers are finding that their loans come with strings—and premiums—attached.

By Rafiq Dar

For many in Jammu and Kashmir, a visit to a local bank branch is an act of trust. Yet, beneath the veneer of “financial inclusion” and the polite smiles of relationship managers lies a growing predatory culture: the aggressive mis-selling of insurance. In a region where economic stability is hard-won, the very institutions meant to safeguard wealth are increasingly accused of depleting it through what critics call “institutionalized coercion.”

The mechanism is simple but lucrative. In J&K, banks have evolved into massive “supermarkets” for insurance products, ranging from life and health to vehicle and credit protection. This shift is fueled by a desperate hunt for non-interest income. Banks earn substantial commissions from insurance partners—funds used to offset rising operational costs like branch rent, employee welfare, and electricity bills. However, the line between a “value-added service” and a “forced sale” has become dangerously thin.

The most pervasive tactic involves the “Profitable Nexus” of loan approvals and insurance policies. In many branches across the Valley and the Jammu division, customers applying for term loans or credit facilities are often met with a subtle form of blackmail. Despite meeting every eligibility criterion, applicants are frequently told that their loan “might not be approved” or will be “delayed by the head office” unless they purchase a specific life or health insurance policy. This practice, known as “tie-in” sales, is explicitly prohibited by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI), yet it remains an open secret in the hallways of regional banks.

Misrepresentation is the second pillar of this crisis. In the race to meet monthly targets, bank employees—many of whom lack deep technical knowledge of insurance—frequently pitch market-linked products (ULIPs) or traditional endowment plans as “guaranteed return” schemes. Customers, often elderly pensioners or small-business owners, are led to believe their money is as safe as a Fixed Deposit, only to discover years later that their capital is subject to market volatility or high premium loads. The “guaranteed” returns promised in a glossy brochure often fail to materialize, leaving families in financial distress.

Health insurance has become another minefield. Unlike specialized insurance agents who might spend hours explaining waiting periods for pre-existing diseases, bank staff often push “one-size-fits-all” group health policies. These policies may seem cheaper but often come with restrictive sub-limits and hidden clauses that compromise family safety when a medical emergency actually strikes. In the high-stress environment of a hospital, many J&K residents find that the policy they bought over a bank counter offers only a fraction of the promised coverage.

The data suggests a deepening problem. Nationwide, the IRDAI’s annual reports have consistently shown that mis-selling remains the primary grievance of policyholders, with banks being a major contributor. In J&K, the lack of financial literacy in rural areas makes the population particularly vulnerable. The “privilege” of getting a loan is framed as a favor from the bank, forcing the borrower into a position of subservience where they feel they cannot say “no” to an unnecessary insurance premium.

So, how can the people of J&K navigate this landscape? The path to financial security requires a return to basics. Financial experts recommend separating banking from insurance. For life coverage, a pure “Term Insurance” policy is often the most cost-effective and transparent option—offering high coverage for a low premium without the confusing “investment” components pushed by banks. For health, individual or family floater plans should be scrutinized for “co-payment” clauses and “room-rent” limits before any documents are signed.

Furthermore, consumers should consider looking beyond bank-led bancassurance. Reaching out to composite license holders or independent financial advisors can provide a broader perspective. These professionals represent multiple companies and can tailor a plan to an individual’s specific needs, often at a discount. Unlike a bank employee who must meet a quota for a single partner company, an independent advisor’s loyalty is—at least in theory—to the client.

The reality in Jammu and Kashmir is that while insurance is a vital tool for peace of mind, the channel through which it is sold matters immensely. As the banking sector faces tighter margins, the pressure to “cross-sell” will only intensify. It is up to the consumer to recognize that a loan is an entitlement based on creditworthiness, not a gift that requires a “thank you” in the form of a high-premium insurance policy. In the world of finance, if a pitch sounds too good to be true, or if a service feels forced, it is usually the customer who pays the price for the bank’s profit.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this newspaper. The author can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply