The Chillai Kalan has passed, but the kitchen fires are burning low. As reliance on sun-dried Hokh Syun reaches its nutritional limit, Kashmir’s farmers look toward modern greenhouses not just for survival, but to break the age-old cycle of winter scarcity.

By Sahil Manzoor Bhatti

The heavy, ominous clouds of Chillai Kalan—the harshest 40-day period of winter have officially parted, marking the end of the valley’s deepest freeze. Yet, for the average consumer in Kashmir, the sigh of relief is premature. While the calendar suggests the worst is over, the ground reality dictates that the valley still faces a grueling stretch of “The Hungry Gap.”

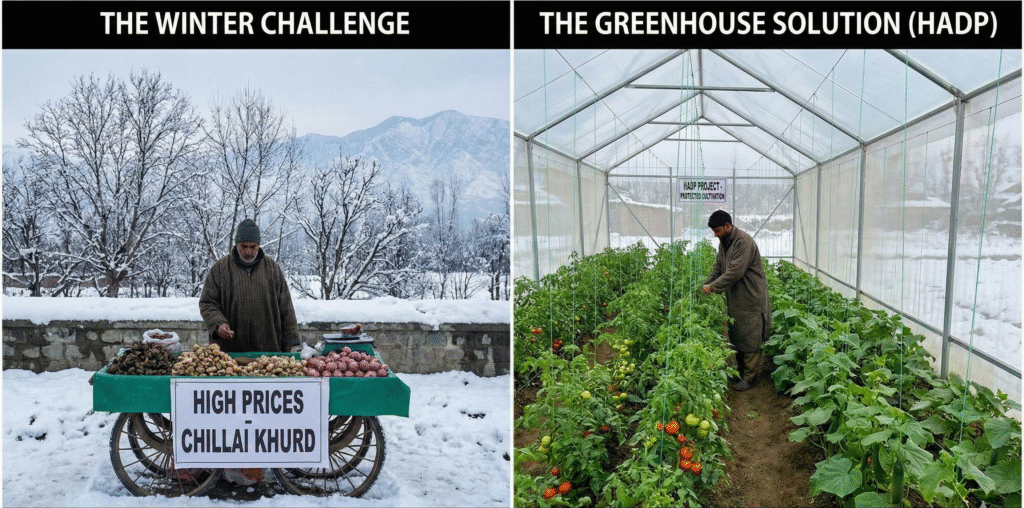

We have entered Chillai Khurd (the 20-day small cold), to be followed by Chillai Bachha (the 10-day baby cold), extending the winter grip well into March. It is during these remaining two months that the true fragility of Kashmir’s food security is exposed. The stocks of dried vegetables stored in autumn are depleting, local fields remain dormant under lingering frost, and the dependence on the unpredictable Jammu-Srinagar National Highway for fresh imports reaches a critical peak.

The Post-Chillai Kalan Price Surge

Walking through the markets of Parimpora or the venders in downtown Srinagar, the economic chill is as biting as the wind. The rates of essential commodities have not stabilized with the end of the 40-day freeze; instead, they have skyrocketed. With the highway frequently disrupted by shooting stones and landslides common in February rains, the supply chain is erratic.

The consumer is left with few alternatives. The reliance on Hokh Syun (sun-dried vegetables) has sustained the population through January, but palate fatigue and dwindling stocks are setting in. While dried bottle gourds and turnips are a cultural staple, the desperate need for fresh, nutrient-rich greens is undeniable. The chilling cold wave may have subsided slightly, but it is still potent enough to spoil fresh produce left exposed, creating a dual crisis of high prices and high wastage.

The Nutrition Deficit

The administration has often emphasized health benefits prior to winter, but the focus must shift to the “Exit Phase” of winter. A recent perspective aligned with data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggests that while dried vegetables provide calories and fiber, the volatile micronutrients—vital for immunity against late-winter flu and infections—are often lost.

As we navigate February and March, the lack of fresh Vitamin C-rich leafy greens becomes a public health concern. The Biodiversity of International Scientists notes that of the 1,100 vegetable species cultivated globally, humans require a diverse intake to maintain health. In Kashmir, during these final two months of winter, that diversity collapses to a handful of expensive imports, leading to sub-clinical nutrient deficiencies across the population.

The Role of Technology

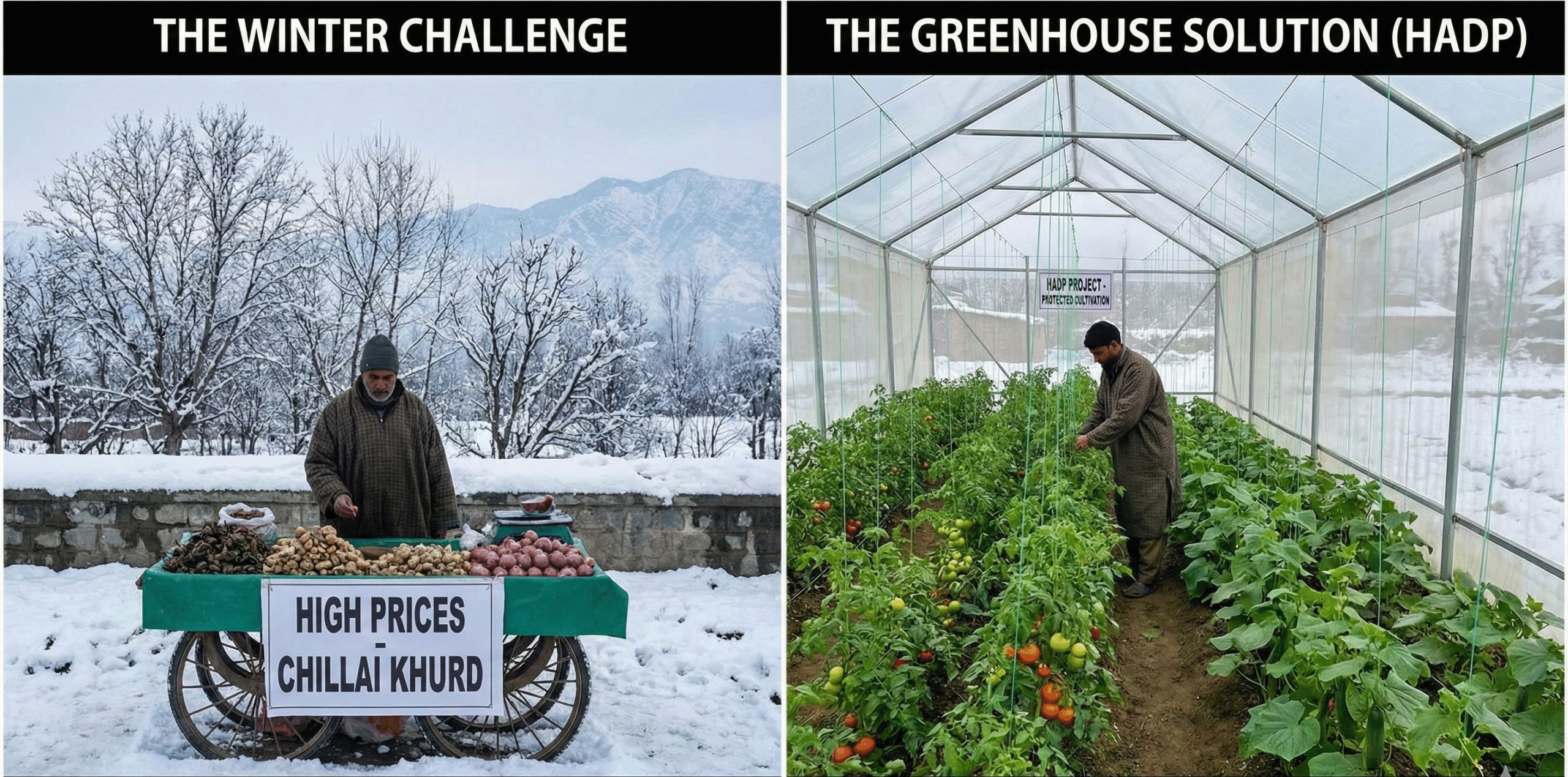

This is where the narrative regarding the Horticulture and Agriculture Departments must shift from “winter survival” to “season extension.” The importance of greenhouse sheds is often misunderstood as merely a tool for the depths of December. However, their true value shines in February and March.

The greenhouse effect, a phenomenon first quantified by Joseph Fourier in 1824, is the key to breaking the cycle of winter inflation. By trapping solar radiation through UV-stabilized cladding, a simple polyhouse can maintain temperatures significantly higher than the ambient air.

In these remaining two months of winter, greenhouses should not just be standing structures; they should be the nurseries of the coming spring. This is the critical window for raising seedlings. If farmers are equipped with functional greenhouses now, they can prepare saplings of tomatoes, cucumbers, and chilies while the soil outside is still freezing. This ensures that when the weather finally turns in April, Kashmir has a “head start” on production, rather than waiting to sow seeds in late spring.

Policy vs. Practice

The government has recognized this gap. The narrative of the “₹10,000 subsidy” is evolving. Under the recently launched Holistic Agriculture Development Programme (HADP), the scale of intervention has grown. The administration is pushing for High-Tech Polyhouses with automated climate control, offering heavy subsidies that dwarf previous schemes.

However, a disconnect remains between the policy documents in the Civil Secretariat and the farmer in the field.

The previous schemes, which required a beneficiary to deposit ₹21,000 to receive a ₹10,000 reimbursement, were often viewed as cumbersome by small-scale growers. While the financial structure is changing to be more favorable, the knowledge transfer is lagging.

Most of our farming community possesses immense generational wisdom but lacks the technical know-how to manage the micro-climate of a polyhouse during the tricky transition from Chillai Kalan to Chillai Khurd. Managing humidity in February is different from managing heat in June. Without proper ventilation strategies, fungal diseases can wipe out an entire crop inside a greenhouse within days—a phenomenon that discourages farmers from adopting the technology.

A Call for “Doorstep Diplomacy” in Agriculture

The Horticulture Department deserves appreciation for its intent, but the execution needs a “journalist’s edit.” Awareness programs held in district centers are insufficient. We need mobile expert teams—agronomy squads—visiting villages right now, during these lean months.

The department must focus on three key areas for the remaining winter:

- Immediate Seedling Distribution: Instead of just seeds, the department should utilize government-run mega-greenhouses to produce seedlings at scale and distribute them to farmers now for protected cultivation.

- Technical Counseling: Farmers need to be taught the “Do’s and Don’ts” of February farming inside a shed. How do you balance the increasing sunlight of late winter with the freezing nights? This technical guidance is currently missing.

- Simplified Access: The requirement for applications on specific paper sizes or bureaucratic loops must be digitized and simplified. A farmer worrying about the frost shouldn’t have to worry about the font size of his application.

Suggestions

The winter is waning, but it is not over. The soil is still cold, and the prices are still hot.

To truly eradicate the shortage of vegetables, the strategy must look beyond just “surviving the snow.” It must focus on empowering the farmer to produce continuously. The government must provide high-quality fertilizers and advanced sprayers now, not wait for the harvest season.

There is a vast potential in the Valley. Our farmers are hardworking; they feed the nation and boost the economy day and night. But hard work without modern tools is a losing battle against the Kashmir winter.

If the Horticulture Department can successfully bridge the gap between the high-tech schemes of the HADP and the mud-boot reality of the village grower, next year we might not be discussing the “skyrocketing rates” of February. We might instead be discussing the “early harvest” of March.

Until then, as we endure the final two months of cold, the greenhouse remains our best hope against the hunger gap—a glass shield against the harsh elements, promising that spring, and fresh vegetables, are just around the corner.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this newspaper. The author can be reached at

[email protected]

Leave a Reply