By Manzoor Akash

Beyond its postcard landscapes and famed hospitality, Kashmir has long been a custodian of traditions that stitched communities together in subtle yet profound ways. One such tradition, now fading into memory, was the ritual of cheese distribution, a practice once common in Kashmiri villages. Known locally as tchamun, this homemade cheese carried with it not only the taste of fresh cow’s milk but also the warmth of neighborly bonds and the values of respect, gratitude, and togetherness.

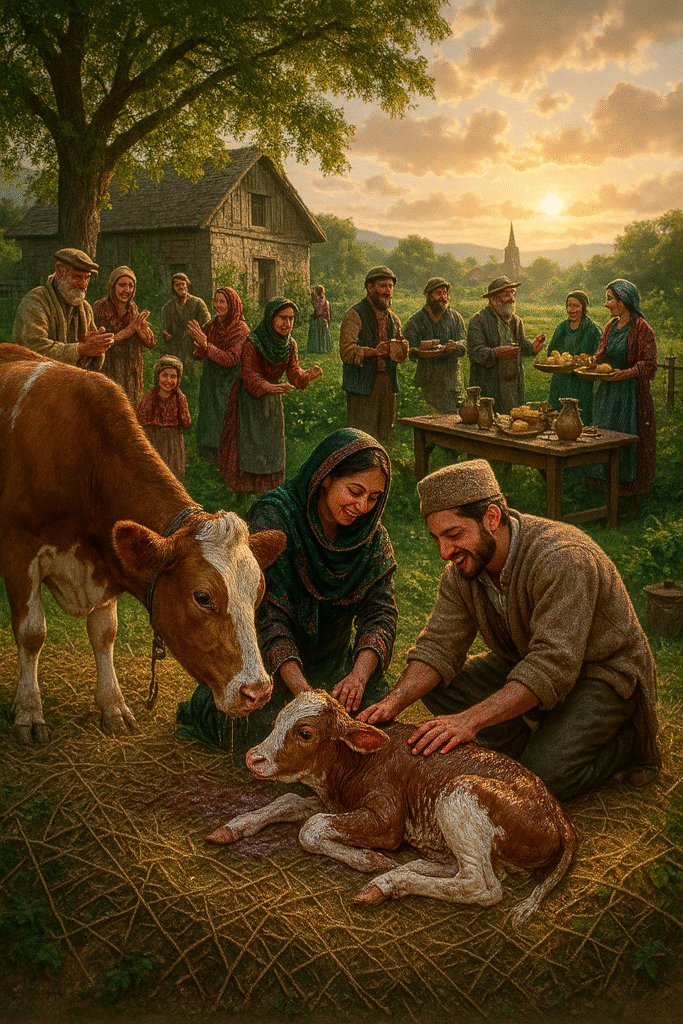

I remember vividly how the birth of a calf was more than just an event at home—it was a celebration. Other chores would be abandoned, as the household’s energy shifted to caring for the cow and preparing for the ritual that followed. For days, milk was collected in large vessels, cherished as a blessing too sacred to waste. From this milk, cheese was carefully made, a process my grandmother performed with both devotion and discipline. She would scold me as a child if even a drop of milk was spilled, reminding me that every bit was precious. My mother, too, inherited this reverence for milk and carried forward the ritual, binding three generations in a chain of continuity.

On the fourth day after the cow’s delivery, the neighborhood would learn of the joyous news—not through words, but through bowls of cheese delivered to their doors. Children, often dressed in pherans even in the summer sun to maintain modesty, were the carriers of this goodwill. The bowls, filled with cheese, would be offered with respect, and in return came small tokens—sugar, salt, eggs, and sometimes money. A ten-rupee note was most common, but a crisp twenty-rupee note felt like a treasure. Along the way, we children often nibbled on sugar crystals or secretly hid eggs, only to face our elders’ reprimands when the truth came out. Yet these moments, half-playful and half-sacred, reflected the joy embedded in this ritual.

The cheese-making did not end with distribution. It was followed by the laborious yet joyous practice of curd churning, locally called gurus-mandun. Traditional tools were used: the motchver (a carafe), the vudh (a stand), and the dhoon (mixer). The vudh, often fashioned from a sheep’s shin bone wrapped in cloth, was tied to the mixer and used to stir the curd. Women would pull the bones rhythmically, creating a chur-chur sound that often made children giggle. What emerged from this process was more than just gurus (skimmed milk) and thi’an (cream); it was an affirmation of communal life, where the very act of sharing became a form of social glue.

The cream that was collected held its own significance. Beyond its culinary use, it was prized for its medicinal and cosmetic value. Women applied it to their skin as a natural remedy for pimples and other ailments, while others used it to smooth their hair before braiding. Every byproduct of milk had a purpose, reinforcing the idea that nothing from this sacred gift should be wasted.

In those times, milk was not a commodity to be purchased in shops—it was a blessing nurtured in one’s own courtyard. Stored in clay pitchers, churned into buttermilk, or mixed with chutney, it was enjoyed in forms that today’s packaged milk could never replicate. The sharing of cheese, milk, and buttermilk across homes was more than an exchange of food; it was a reaffirmation of trust, affection, and collective responsibility.

But like many traditions rooted in rural life, the cheese distribution ritual has largely disappeared. The transformation has been quiet yet profound. Education, economic progress, and changing lifestyles have redefined the way people perceive community. The upward mobility of households, access to packaged dairy products, and the convenience-driven rhythm of modern life have all contributed to the decline of this practice. What was once a symbol of interdependence has been replaced by individualism and consumerism.

Still, the fading of this tradition should not be read merely as loss. It is also a reminder of what made Kashmiri society resilient and unique: its ability to weave everyday acts into cultural rituals. The cheese distribution ritual was not about luxury; it was about respect for sustenance and gratitude for life. It was about embedding joy in the ordinary, and solidarity in the smallest gestures.

Today, as Kashmir looks toward the future with aspirations of development, modernization, and global connectivity, it also faces the challenge of preserving the threads of its cultural heritage. Traditions like tchamun may no longer be practical in their original form, but their spirit can inspire newer ways of fostering community bonds. Reviving cultural practices, documenting them, or adapting them into contemporary forms can help ensure that these stories do not vanish into silence.

The story of Kashmiri cheese distribution is not simply a quaint memory of the past—it is a cultural narrative that speaks to values of gratitude, sharing, and humility. In remembering it, perhaps we also find a way to remind ourselves that progress and tradition are not opposites, but can walk hand in hand. The bowls of cheese may no longer arrive at neighbors’ doors, but the essence of the ritual—love, respect, and unity—remains timeless, waiting to be rediscovered.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this newspaper. The author can be reached at [email protected]